Silvertown

Industrial sites and ruins have inspired film makers and artists for generations with their ability to suggest dystopian landscapes and uncertain futures.

The SILVERTOWN project was inspired by a vast industrial complex which operated from the 1870’s to the 1960’s on the banks of the Thames in East London. As is common in Victorian architecture, the site was littered with architectural features plagiarised from a wide range of styles; Italian cherubs decorated buildings where toxic chemicals such as Naphtha and Toluene were once refined from coal. The early days of the site coincided with the Arts and Crafts movement championed by William Morris whih flourished at this time, motivated partly by a reaction against the rise of industry, and advocating a return to craft and to individual practice. Paradoxically perhaps, the movement was much patronised by the industrial leaders of the day.

The area was severely bombed during the war and for many years after its closure it remained a spectacular ruin, attracting film makers such as Stanley Kubrick (Full Metal Jacket) and Michael Radford (George Orwell’s 1984).

The Silvertown site has now utterly vanished under shopping malls and gated communities and no longer registers on present day maps of the area. It is now a place that exists only in the imagination and in the films and artworks it inspired. The memory of the site and its representations reiterate how stories and histories of all kinds attach themselves to specific locations over time, re-appearing as the fragments which form our collective memory of the past.

The complicated exchange between art and commerce has continued down the years and is perhaps echoed in JSW’s generous offer to Srishti students to visit the biggest steelworks in India – interspersed with trips to Hampi. This trip has formed the basis of this current incarnation of the project. The extreme contrast between these two locations has inspired students to produce some engaging and original work. After the initial impulse to document everything these two dramatic locations have to offer with photographs, video and sound recordings; more developed and considered work has emerged, with varied and original presentations adding new layers of meaning.

The currency of art is and its relation to business and heritage is perfectly rendered by Natasha Ranganath and Nandini Bhotika’s scrap metal medallions which bear their illustrations of the story of Sugreeva and Vali’s battle as described in the Ramayana. JSW are currently supporting the restoration the Hanuman Temple on the banks of the Tungubadra river, the location of Hanuman and Rama’s first meeting. Identification with great empires and myths of the past bestow authenticity and gravitas on organisations, aligning them with treasured national narratives, adding a more colourful and evocative persona to descendants of the Industrial revolution.

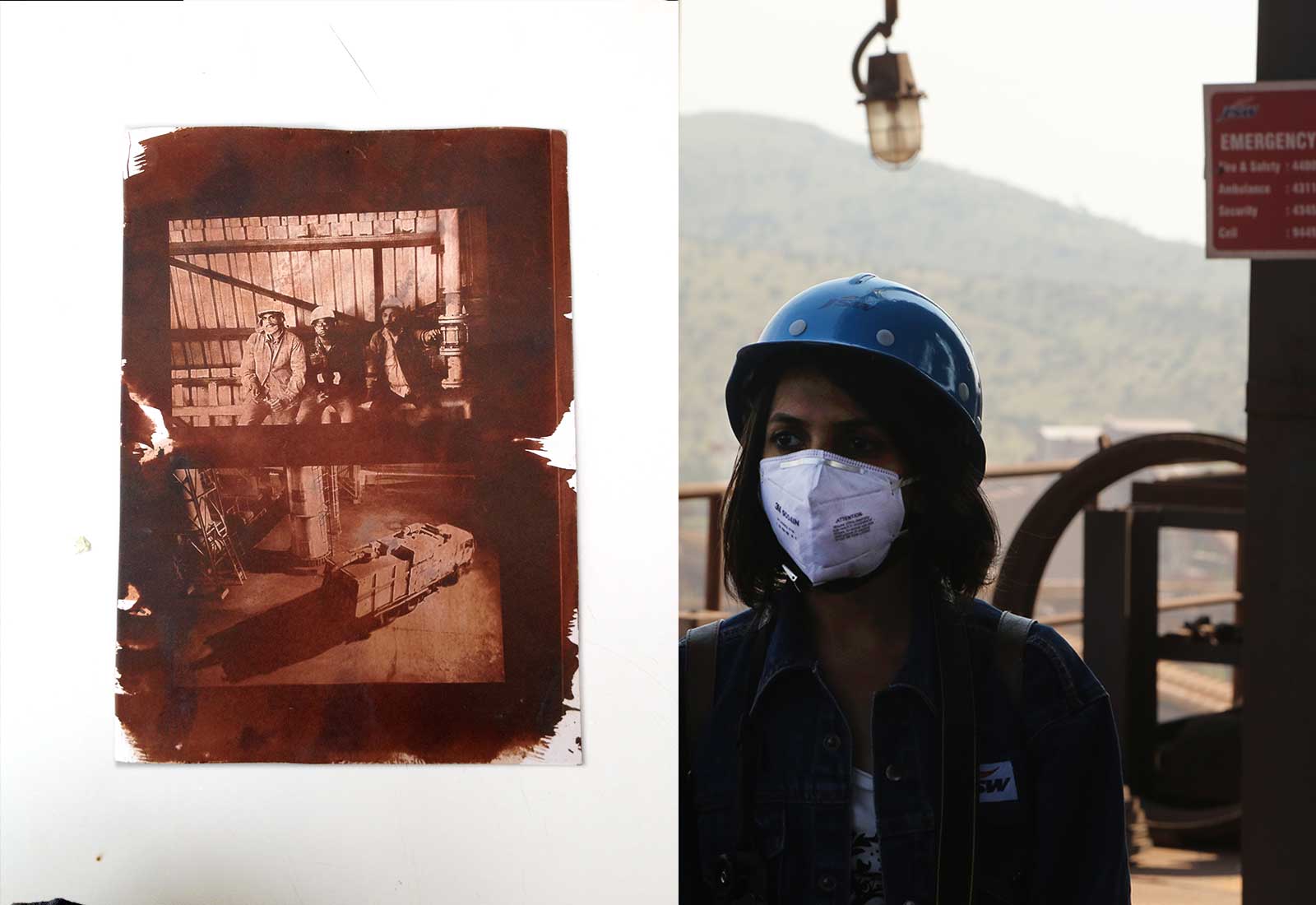

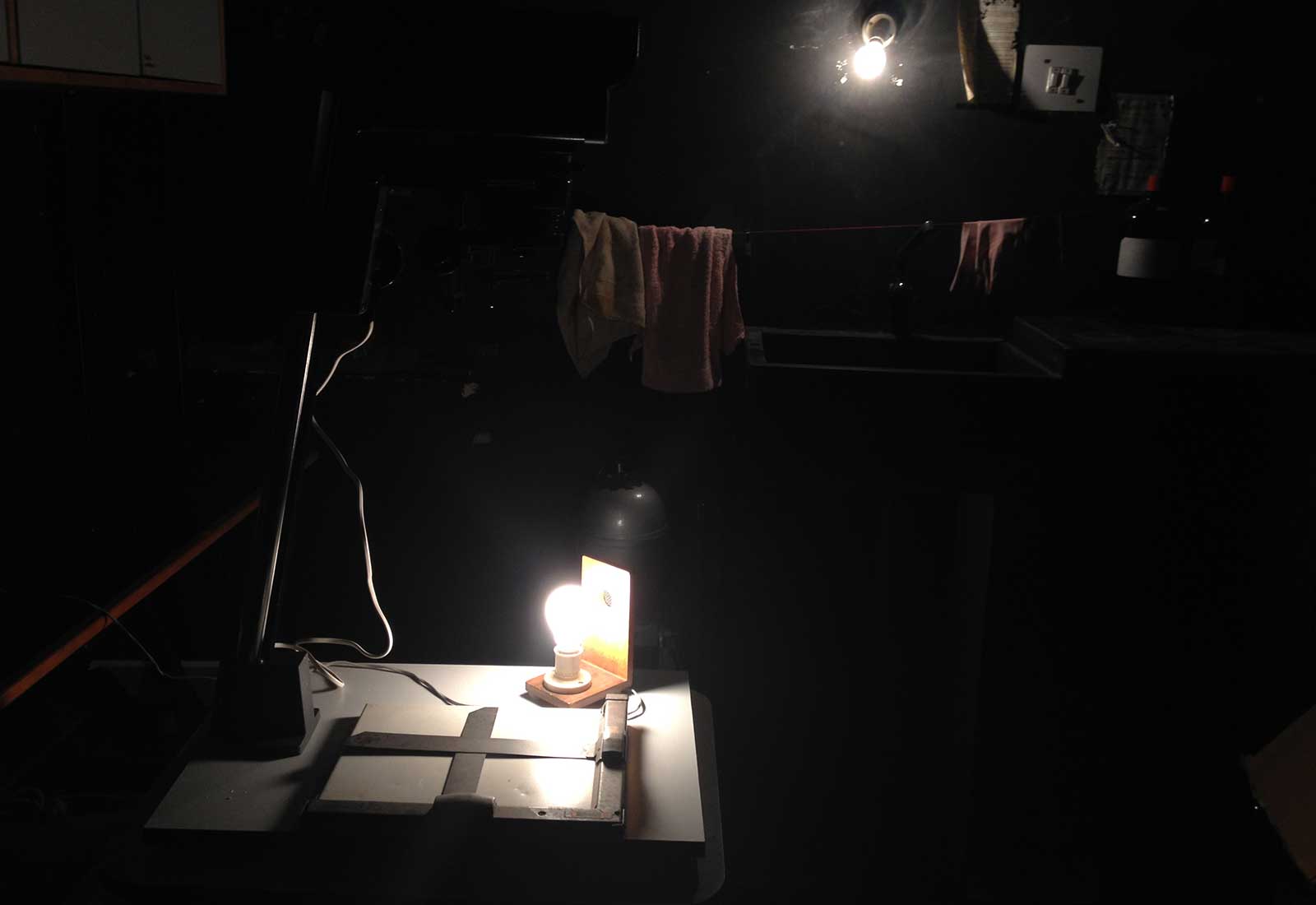

Much of the work in this exhibition reflects a renewed and widespread interest in the use of historical photographic processes, such as salt prints, cyanotypes and liquid emulsion by practitioners keen to capitalise on the expressive capabilities and abstract potential of these processes.

Nitya Balakrishna and Mokshaa Vohra’s decision to print stock library images of Hampi using liquid emulsion on 5×4 glass plates, rather than using their own photographs, highlights the relationship between redundant technologies and present day cameras which come primed with the expectation that tourists will ‘consume’ historical sites through photographing them, despite of an almost inexhaustible supply of similar images..

Other works employ digital technologies such as Utkarsh’s evocative film which foregrounds the use of the still image in video combining industrial footage with a soundtrack featuring a group of chanting women recorded at Hampi, mixed with the ambient sounds of the area.

Sanjana Raju’s book Mismatched offers acutely observed details from the two locations demonstrating a measured interest in both – a personal vision more concerned with image making than with merely recording the surroundings.

Sohini Mukhergee and Shyamolie Kate’s book focuses on tourists and workers by removing them from the backgrounds in which they were photographed – a strategy which emphasises their existence as individuals rather than as a part of the environment in which they are encountered.

Param and Madhulika’s display of chemical prints offer a vision of the two locations which is at once contemporary and historical. This presentation offers a tactile and expressive print quality ver distinct from the products of multi-national imaging companies, committed to promoting more precise but perhaps more anodyne renderings of the world in which we live.

Through these impressions Silvertown becomes an imaginary atlas – an image of the world we hold in our imaginations, built from personal memory, history and myth and viewed through the lense of current concerns.

Allan F. Parker – Dec 2014